The disturbing truth behind the Royal Navy’s failure to prevent Somali pirates kidnapping a British couple from their yacht can be revealed today.

An investigation by The Mail on Sunday demolishes accounts by the Ministry of Defence and the head of the Navy which suggest that a naval vessel at the scene had no rescue force available.

In fact, far from being a toothless bystander, the Royal Fleet Auxiliary ship Wave Knight was within seconds of unleashing a crack team of 20 lethally armed Royal Marines.

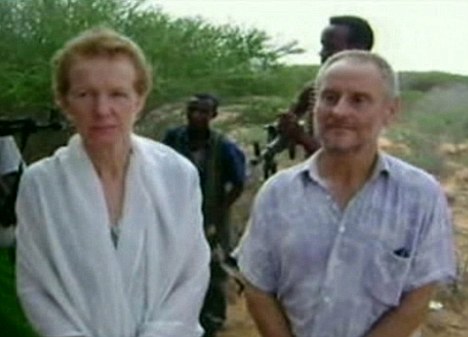

So close to freedom: The Chandlers are still in captivity. They have been filmed saying they were ‘unharmed’ but that their captors were losing patience

Wave Knight’s crew have been so angered by the official portrayal of events that one witness has given us a career-risking statement.

His evidence raises troubling questions about Government and military policy on piracy. And many people will want to know why an elite commando troop, mustered in black combat fatigues only yards from the kidnappers, was not permitted to put its air and seaborne assault training into action.

The astonishing stand-off occurred on day six of the hostage crisis as the pirates attempted to transfer Paul Chandler, 59, and his wife, Rachel, 55, to their mother ship.

Witness: The military ship RFA Wave Knight which allegedly watched as the Chandlers were taken captive by Somalian pirates

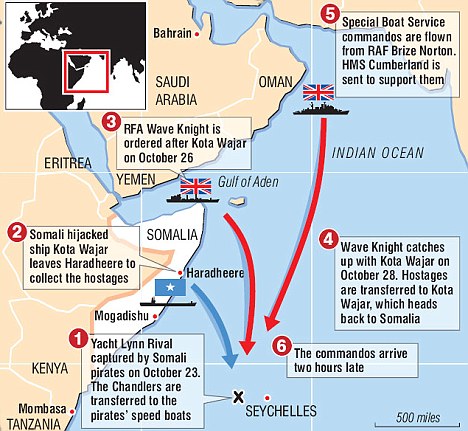

The Chandlers had been seized early on October 23 as they tried to sail their yacht, Lynn Rival, from the Seychelles across the Indian Ocean to Tanzania.

The couple no doubt believed their voyage was safe. In the past, Somali pirates have operated closer to their home ports some 1,000 miles north.

But increasing anti-piracy patrols by Nato and other navies have pushed them south to seek new hunting grounds, and armed pirates aboard at least two fast motorised skiffs ambushed them only 150 miles into the trip.

The Chandlers, from Tunbridge Wells, Kent, managed to send out a distress call but were quickly overpowered.

The Chandlers' yacht, lashed to the deck of the Wave Knight

Realising it would take too long and be too risky to sail Lynn Rival back to northern Somalia, the kidnappers radioed for support from one of the country’s most notorious pirate ‘nests’ – Haradheere.

Within 72 hours, accomplices were sailing south in the 24,000-ton container vessel Kota Wajar, itself hijacked while en route from Shanghai to Kenya on October 15.

On October 26, the commander of Wave Knight, Captain Clarke, was briefed on the crisis. Intelligence sources had uncovered Kota Wajar’s role as mother ship to the kidnappers and she was being tracked.

As the closest Royal Navy ship available, Wave Knight was ordered to find her and slow her down by any means. A Wave class supply ship, she is mostly crewed by 75 civilians working under military discipline.

‘They had just trained for exactly this scenario’

However, crucially, Captain Clarke had on board the Marines, a Merlin helicopter and firepower in the form of 30mm and 50mm cannons. Around 25 Royal Navy sailors were also present.

The MoD’s first version of events avoided mentioning any chase, confrontation or rescue plan. This was all air-brushed out of the official picture – along with the Marines.

Indeed, the MoD at first acknowledged simply that an unnamed Royal Navy vessel had come across the Chandlers’ empty yacht. Only after the Daily Mail revealed that Wave Knight was almost alongside the Chandlers, her crew watching as the couple were hustled aboard the Kota Wajar, did the MoD change stance.

The yacht belonging to Paul and Rachel Chandler being unloaded at Portland Port in Dorset

A second, carefully worded statement then claimed that ‘everything possible was done without further endangering the lives of Paul and Rachel Chandler’.

It added: ‘We do not comment on operational detail but RFA Wave Knight did very well under the circumstances.’

Days later, the head of the Navy, Admiral Sir Mark Stanhope, went further, insisting that Wave Knight’s ‘sailors with pistols couldn’t do the job of ensuring the safety of the Chandlers’.

And even last week he insisted that everything possible had been done to rescue the Chandlers.

In a speech at Chatham House, he said: ‘Wave Knight did exactly the right thing… Had there been an opportunity to intervene, while being sure of guaranteeing Paul and Rachel Chandlers’ safety, they would have done so.’

In fact, according to our source, these official explanations are travesties of the truth. His account states that Wave Knight left her British base at Bahrain around October 14 and headed south into the Gulf of Aden’s so-called ‘pirate alley’.

Her role included servicing and refuelling ships from Nato’s task force but she was also fully equipped for boarding operations.

As news of the Chandlers’ kidnap spread around the world, the crew kept in touch with developments via news websites. On October 26, Captain Clarke issued a loudspeaker announcement, or ‘information pipe’, explaining that they were heading south – away from traditional pirate waters. Although he didn’t mention the Lynn Rival by name, our source says it was obvious to the crew that a rescue attempt was ‘on the cards’.

The 31,500-ton Wave Knight sighted the Kota Wajar on the evening of October 28 and immediately tried to intimidate her by closing to less than 100 yards. At this point the Lynn Rival was not in sight so there were no hostages on board the pirate ship.

The supply ship was ‘closed up’ for action – meaning that all hatches, doors and gun emplacements were sealed with personnel out of sight. Lights were extinguished except for the powerful searchlights raking back and forth across the Kota Wajar’s hull.

At first the pirates appeared to be unconcerned. Their vessel was, in the source’s words, ‘lit up like a Christmas tree’ for the first 30 minutes.

But suddenly it, too, snapped out its lights and the two ships steamed alongside each other in darkness.

Kidnapped: Paul and Rachel Chandler were sailing around the world when their boat was hijacked by Somalian pirates

But Wave Knight’s tactics had no effect. Even warning bursts from one of her two bridge cannons, which fire 30mm shells with the power to penetrate the hull of a small air or sea craft, failed to alter the pirates’ course or speed.

The cannons have a range of about a mile and can fire up to 1,000 rounds a minute travelling at 600 yards per second. Undeterred, the pirates returned fire using small arms and the cat-and-mouse confrontation continued.

According to the source, it now became clear that the Marines were preparing for action. They had just completed two weeks of intensive training for precisely the scenario they faced – an air and seaborne assault on a pirate vessel.

‘In horror and disbelief, Wave Knight’s crew watched as a line was thrown from the Lynn Rival’

The Wave Knight and the Kota Wajar were still some distance from the Lynn Rival and Chandlers, so there was no danger of the hostages being caught in crossfire.

Like all the ship’s military personnel they had been on a state of permanent readiness, known as ‘Alert 60’, for two weeks. This required that they could muster within an hour.

Twice that night, between 10pm and 1am, they went a step further. On each occasion the codeword indicating imminent action – Quickdraw – was repeated over the ship’s intercom.

Each time the Marines gathered quickly on deck, their all-black fatigues, balaclavas, night-vision goggles and carbines a picture of professional menace.

Close by, Royal Navy aircrew sat at the controls of the Merlin awaiting their start-up order.

This picture taken from the Wave Knight shows the Chandlers' yacht drifting - and HMS Cumberland, which arrived too late

The ship’s gun teams – who are also armed with general purpose machine guns firing 7.62mm rounds at up to 950 per minute with a range of 4,000 yards – stared out at target areas on the Kota Wajar.

But on each occasion the assault team – part of the Royal Marines Fleet Protection Group based at Faslane on the River Clyde – was stood down.

According to our source the pirates, still apparently believing that they were up against a mere supply ship, appeared almost contemptuous when they finally drew alongside the Chandlers’ yacht and hailed the kidnappers on board.

In horror and disbelief, Wave Knight’s crew watched as a line was thrown from the Lynn Rival. The yacht was then casually hauled in and moored alongside the Kota Wajar together with the pirate skiffs.

Throughout this 20-minute period, the Chandlers and their captors could be fleetingly glimpsed as shadows and silhouettes in the supply ship’s searchlight.

Although the Wave Knight remained darkened, it is inconceivable that the couple could have mistaken it for anything other than a naval vessel and perhaps dared to hope a rescue was imminent.

In the sweltering night, illuminated only by the stars and sweeps of the Wave Knight’s searchlights, the Chandlers could be seen climbing a ladder on the side of the Kota Wajar, with pirate guards above and below them.

Then they disappeared into the ship’s hull. The Kota Wajar turned and steamed slowly north with its hostages.

It was, according to our source, a surreal moment. Having been feet away, poised for a dramatic rescue, some of the world’s most feared fighting troops were now being ordered to pack their kit and go to bed.

A pursuit of the Kota Wajar was, apparently, deemed pointless.

The source added: ‘The mood among the Marines was one of intense anger and frustration. These guys were right up for it – absolutely champing at the bit. It was precisely the situation they had trained for.

‘We had all watched them practising rapid-roping [descending at speed on ropes from a helicopter] and sea-borne assaults. They knew exactly what to do. They were poised there like a bunch of Ninjas and the adrenaline was pumping.

‘They couldn’t believe the orders to stand down. The anger was obvious. I heard one joke later that they had all the gear while Northwood [UK command HQ] had no idea. We had a chance to strike a real blow at the pirates and send a message that you don’t mess with the Royal Navy.

Ready for action: Royal Marines were poised to stage a dramatic rescue but were stood down

‘Judging by its actions, the Kota Wajar had no idea who we had on board. They thought we were just a supply ship. There was a great opportunity to take them by surprise.’

The source recalled seeing the silhouettes of the pirates and the Chandlers being taken off the yacht.

‘The Marines were saying, “Now’s the time. Surely it’s got to be now.” But the order never came.

‘The Kota Wajar just sailed off slowly as if to say, “You can’t touch us now. We’ve got the hostages.” They knew they’d won.’

The crew member added: ‘The Marines were more than capable of seizing the Kota Wajar way before she got near the Chandlers.

‘At that time there were no hostages on board. You can argue that the Chandlers would still have been at risk from the pirates on their yacht. But we would have been in a strong position, having taken the Kota Wajar.

‘If the pirates had killed the Chandlers they would have had nothing and would have been totally exposed. It’s more likely that they would have negotiated a hostage exchange for their mother-ship and crew.

‘No rescue was without risk. But the Marines were in a great position and were never allowed to exploit it.’

The crew member is unsure precisely what weapons the Marines were carrying. But the Fleet Protection Group’s standard issue includes SA80 assault rifles, SA80A2K carbines, MP5a3 9mm sub-machine guns and high-power 9mm Browning pistols.

It can also deploy specialist marksmen known as Maritime Sniper Teams, skilled at ‘slotting’ enemy forces from distance. It is unclear whether an MST was present.

‘A 20-strong SBS team arrived two hours late’

As dawn broke, the crew of the Wave Knight sighted their flagship, HMS Cumberland. The frigate had arrived some two hours after the Kota Wajar’s departure.

Between the two vessels the abandoned Lynn Rival drifted ghost-like on the breeze. She was eventually hauled on to Wave Knight.

According to our source, the Navy’s refusal to attempt a rescue of the Chandlers appears to have been at least partly influenced by plans for a covert operation involving HMS Cumberland and a Special Boat Service troop.

He says the idea was to parachute 20 SBS men from a military transport plane into the sea off the Somali coast. They were to be picked up by Cumberland – whose movements throughout have never been revealed – to lead a rescue attempt.

Sailing enthusiasts: The Chandlers are believed to have been captured by Somali pirates while sailing between the Seychelles and Tanzania

However, the source claims the plan went disastrously wrong from the off. He says the SBS team, assembled at RAF Brize Norton, was delayed for around six hours due to ‘unforeseen events’. By the time Cumberland picked them up from the drop zone they were at least two hours behind the action.

Wave Knight ferried the SBS team – complete with parachutes, arms and equipment – 1,000 miles north to the Omani port of Salalah. It was during this trip, says the source, that nuggets of information emerged from the SBS men in Wave Knight’s mess rooms.

They were, he says, appalled at the lack of flexibility among senior commanders to adapt the rescue plan and send in the Marines.

Within hours this sense of frustration was heightened further. The source says that en route to Oman, the supply ship came across another pirate vessel – little more than the size of a tug – which opened fire on them.

‘It makes you wonder, what is the Royal Navy for?’

By now Wave Knight had 20 Marines and 20 SBS soldiers on board – arguably the most lethal assault force of any Nato vessel in the anti-piracy operation. The pirates had no known hostages aboard.

An assault party was placed on ‘Quickdraw’ alert and expectation rose among the crew that at last action was imminent.

Our source said: ‘We thought it was inevitable. Pirates had fired first at a Royal Navy ship. If this doesn’t satisfy the Rules of Engagement, then what does?

The pirates wouldn’t have done that to an American ship because the Americans shoot back – with interest.

We had all the firepower and expertise we needed several times over. Yet again the order came to stand down. It makes you wonder, what is the Royal Navy for?’

Deserted: The Chandlers' 38ft yacht Lynn Rival, pictured here being fixed before their ill-fated trip, was found abandoned by Royal Navy forces patrolling the pirate-infested waters off Somalia

The SBS force was flown off Wave Knight by helicopter on November 1, landing in Salalah. A military transport plane immediately returned them to the UK.

Frustration among Wave Knight’s crew was not lost on senior commanders and early that morning Captain Clarke included a long, personal communique to the entire company in his Daily Orders.

The document confirms the presence of Royal Marines but refers to the SBS only as ‘embarked forces’. It is headed: ‘Command Aim TLC [Tender Loving Care] for embarked forces and make preparations for the safe and timely disembarkation of RM [Royal Marine] passengers and 814 Sqn Det [Merlin helicopter crew].’

The captain passed on congratulations from commanders at Northwood, near London, the Navy’s operational HQ and home of the Armed Forces Permanent Joint Headquarters, which controls all UK overseas operations.

They emphasised that the ship’s conduct was a ‘success story’, despite Northwood’s refusal to sanction a Marine rescue attempt.

After disembarking the SBS, Wave Knight headed back to the UK Maritime Component Command base in Bahrain, where 25 Royal Navy crew were landed.

The ship went on to Cyprus, where most of the Marines were dropped off for a week’s leave before being re-deployed or returning to their families.

She then returned to the UK, docking last Thursday in Portland, Dorset, with only her 75 civilian crew aboard.

Adventurers: Rachel and Paul had embarked on numerous trips aboard their yacht, Lynn Rival

The Lynn Rival, which had been stashed on Wave Knight’s deck as our exclusive picture shows, was craned into the sea, then lifted on to a lorry and transported under cover to an unknown destination.

The Mail on Sunday’s revelations are certain to increase pressure on Admiral Stanhope to explain why he made an apparently misleading statement to The Times – an interview reprinted by other newspapers – on November 18.

His quote reads: ‘Two dead Chandlers would not have been good, and we wouldn’t have wanted to be part of that… It’s a huge piece of water and the fact that Wave Knight found the yacht was impressive, but we were not in a position to engage [the pirates]. We were too late for that.

‘You need special expertise to deal with hostage rescue, and we didn’t have that expertise [on board].

‘Sailors with pistols couldn’t do the job of ensuring the safety of the Chandlers. It was highly frustrating. There were broad rules of engagement that had to be followed, and it was a fairly easy decision to make because the security of the Chandlers was the most important thing.’

He added: ‘What could it [Wave Knight] do under the circumstances? Wave Knight is not a warship. There was only a flight [helicopter crew and engineers] on board, and as soon as they got close, the pirates threatened the hostages. They did the best they could, but the security of the Chandlers was the overriding factor.’

Last Friday he repeated his view in a speech at Chatham House, London, saying: ‘The sailors did a tremendous job in finding the Chandlers’ yacht in the first place. But once you have a hostage situation your military options, as most people would understand, are inevitably limited.

‘Had there been an opportunity to intervene, while being sure of guaranteeing the Chandlers’ safety, they would have done so. The decision not to was undoubtedly the right one.’

A senior Royal Navy source insisted last night that there were ten Marines on board Wave Knight, not 20.

An MoD spokesman said: ‘The First Sea Lord has always been clear that Wave Knight and those in command of this mission did exactly the right things.

‘As in all situations of this sort they had to balance capabilities and possible actions against the risk to life.

‘They did everything that they could in that operation and, could action have been taken, with a guarantee on the safety of the Chandlers, they would have done so.

‘Previous statements have only concerned detail that is already in the public domain, or would not be of use to the pirates we are trying to counter. We will not comment further on this detail. Discussing our capabilities in this way could reveal valuable information.’

For the Royal Marines and crew of the Wave Knight, those words surely carry a hollow ring.

As for the Chandlers, whose lives are being ransomed in Somalia for £4million, the agonising memory of October 28 is unlikely to fade soon.

They saw the Navy come to their rescue and then sink their hopes.

This article was sourced from www.dailymail.co.uk

Tags: kidnapped british sailors, Lynn Rival, paul chandler, royal marines, somali pirates

Well, well… I believe the Royal Navy messed this up very well.

No reason to start the blame game, as I believe everyone seeing this case understands the mistakes done already.

Allow me to suggest that the UK Navy look at for example the French and USA navy’s actions when their nationals where taken hostage. That might teach the UK Navy/Government a lesion, or will it? The UK claim to have a superior armed force, but is it really true? I think so, but someone need to manage it and take decisions, or the UK might waste its resources and talents.

The French acted quickly and freed one lot of hostages and recuperated parts of the ransom; suggest everyone (especially the UK MoD) look at the documentary film. The second action had a part fatal end, but the French acted!!!!!!

The USA acted as well and they recuperated the captain of the Maersk Alabama and shot and captured the pirates.

Well dear UK Navy, are there lesions to be learned? I do think so!

Paul and Rachael, should not be in Somali now.

Did you fail?

With respect, I might be inclined to think you failed. And perhaps you should look at the French and the USA and take quick and decisive action in future.

Also please get going to release Paul and Rachael! I believe you have a special force, etc. So use it and you can easily get the Somali Governments approval to do whatever you need.

Again look at the France, they obtained quickly permission from the Somali government to do whatever was needed even on Somali land.

Get going before you will be sorry and Paul and Rachael will be gone.

Paul in Luxembourg

It is now a very long time since anything has been heard of Paul and Rachael Chandler who were kidnapped by Somali pirates. No doubt they are now dead. In my opinion those in authority in the War Office who were responsible for this disgraceful affair should be arrested and charged with conduct unbecoming to their position, at least.

The whole episode fills me with nausia and also a sense of utter disgust at the decision of the War Office in this matter.